Welcome to Lit Review, where columnist Dominiq Wilson will take apart a series of chapbooks to figure out what works and what doesn’t for the modern reader of poetry.

Before continuing this review, I want to make readers aware that this book discusses adult themes such as sexual assault and rape. For readers who are sensitive to these topics, I advise that you approach this book cautiously, if at all. —DW

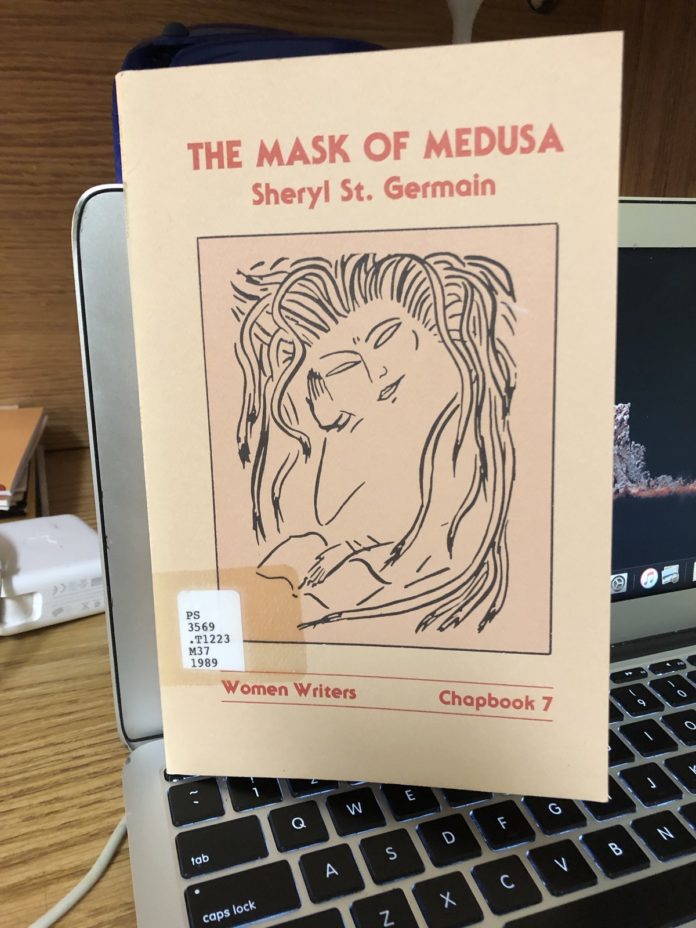

“The Mask of Medusa” is a collection of 36 poems, published in 1987, written by Sheryl St. Germain and illustrated by Janet Morgan. This is the seventh chapbook within the Cross-Cultural Review Women Writers Chapbook Series, which aims to focus and expose women’s writing that has strong cultural ties or addresses women’s issues.

The collection’s title is a strong indicator to the subject of these poems, and, knowing what social commentaries this book is presenting, I found it interesting that Medusa was declared the mythological spokesperson of women’s rights. However, after reading these poems, it’s easy to apply the events in her life to issues faced by women from 1987 to present day. Take “Medusa Has a C-Section” for example:

You come prepared to watch the whole bloody thing,

but when they begin to cut into my belly

I see your eyes travel upwards

to the mirror on the ceiling reflecting everything.

I think of all the times we made love

with you watching everything in a mirror.

The mirror was always, always between us,

even when we thought we were touching.

Your mirrored gaze and this birth by knife

remind me of that other birth by sword:

the polished shield held up between two lovers

reflecting the sword severing the head

cleanly from the body, the children

leaping from the wound.

I hear their cries inside me

before my head falls.

I found this poem very intricate in its layout. Both stanzas obviously discuss two separate events—a c-section and Medusa’s beheading, respectively—but both events are connected by the object of mirrors between two bodies. With the information I can grasp from this poem, they also seem to be connected by the same man who is the father of her children and her killer. I recall Perseus being her killer, but I don’t know much about Medusa being his lover.

Though Medusa is often portrayed as having a villainous personality, I’ve always liked her and appreciated the powers that she was cursed with. I like to compare her to Ursula from The Little Mermaid, another favorite character of mine who uses her supernatural and slightly villainous powers to pleasure herself instead of others.

This being said, there were a few poems I adored in this collection that portrayed Medusa as something other than this powerfully villainous woman. “Medusa Dreams of Red Tulips” portrays Medusa in a more self-conscious light. The poem takes up a whole page with a description of Medusa’s dream of her snakes being turned into tulips and how the night with a lover would go. “Medusa Falls in Love” reads from the perspective of her finding love at first sight and how her frozen state compares to the nature of her powers.

On the other side of this coin, there are plenty of poems in this collection that reflect the sassy personality I expect from Medusa. “Medusa Goes to a Restaurant” is relatively short and simple. It seems to be her half of a conversation with a waiter who is concerned about her stone eyes. However, my favorite poem in this collection is Medusa’s piece of a conversation with Sigmund Freud. If you’re familiar with his contributions to the social sciences, I think you’ll enjoy “Medusa Has a Breakfast with Freud” below:

Do you like your bacon crisp or limp?

Oh, and I wish you would make up your mind:

either my snakes are pubic hairs or penises,

either you get stiff with an erection

or frozen with impotency

when you look at my face. I’ll have

no either/or here.

(Have you ever noticed

that everything you look

at turns to sex?)

By the way, how do you like your genitals—

scrambled or fried?

I almost wish that St. Germain left out the parenthesized stanza, so the theme of the poem would be more of an inside joke for everyone who knows of Freud’s work. But after typing it out just now, I realized that Medusa is comparing Freud’s universal application of sex to her ability to turn people to stone with one look. I’d love to read a poem that showed Freud’s response to this, but I also think that if given the opportunity, a lot of people would like to ask him the same question. An interesting man, Freud was.

I’m really happy that I had the opportunity to read this book, and the last two or so poems wrapped the collection up as if every poem contributed to a larger story, which I also enjoyed. As usual, I strongly recommend that you take some time to read this collection for yourself. I hashed this book out in under an hour, but if you have the opportunity, I suggest that you space this book out a bit more. I will admit that it can get pretty intense at times.

If you’re interested in reading this book, you can pick it up at our campus library, or buy it for around $8.