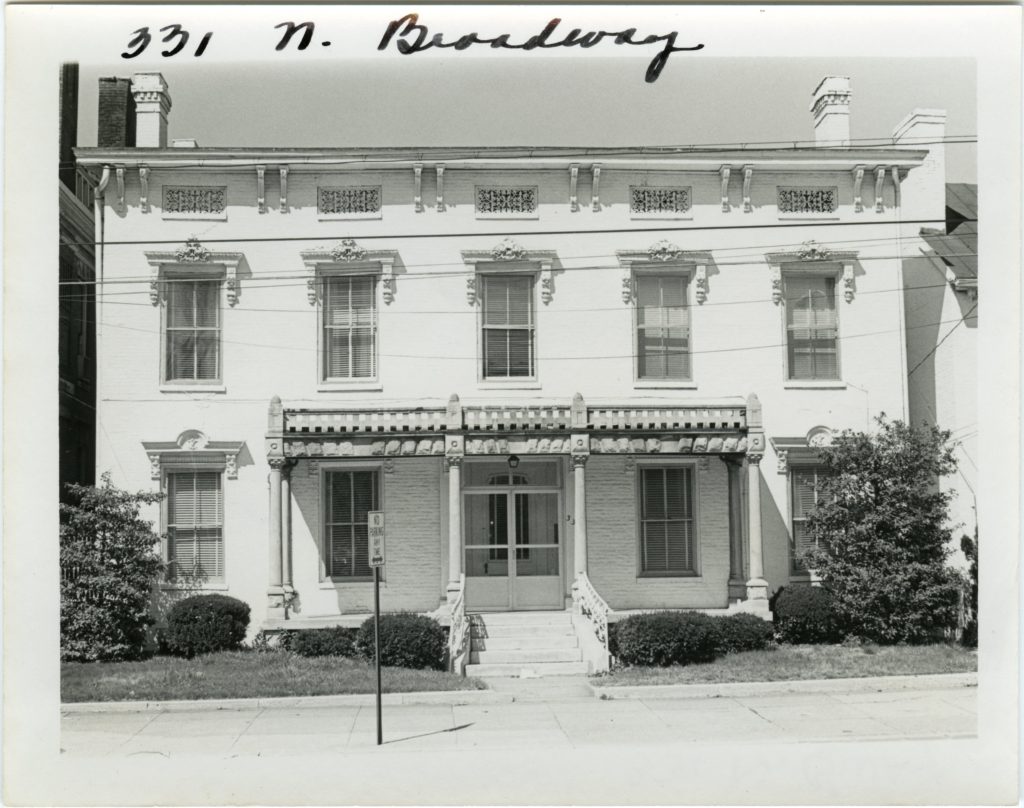

331 North Broadway: you might know it as the International House, or as the house where The Rambler’s editor-in-chief lives. Or, you might not know the house at all.

331 is located right on Broadway, next door to Forrer Hall. As of last year, it was no longer called the International House, because the language learning requirement no longer applied. It contains four living units, each housing four people.

One day this summer, one of my roommates sent a group-text, and I’ll paraphrase: “I was doing some research on our house, and found out it used to be a black college!”

A conversation about ghosts ensued, but my curiosity was sparked in a way only a journalist’s mind would be. Was this true? How old is our house, anyway? Who used to live here?

I decided to pursue these questions and research the history of the house at 331 North Broadway. What followed was an action-packed trek through layers of Lexington history, filled with cemetery hunts, archive searches and cold phone calls to non-existent lawyers. This is the story of my search, and the fascinating history it revealed about the house, the Northside neighborhood, and even Transylvania itself.

First searches, first residents

I started where any millennial might: typing “331 North Broadway Lexington history” into a search bar.

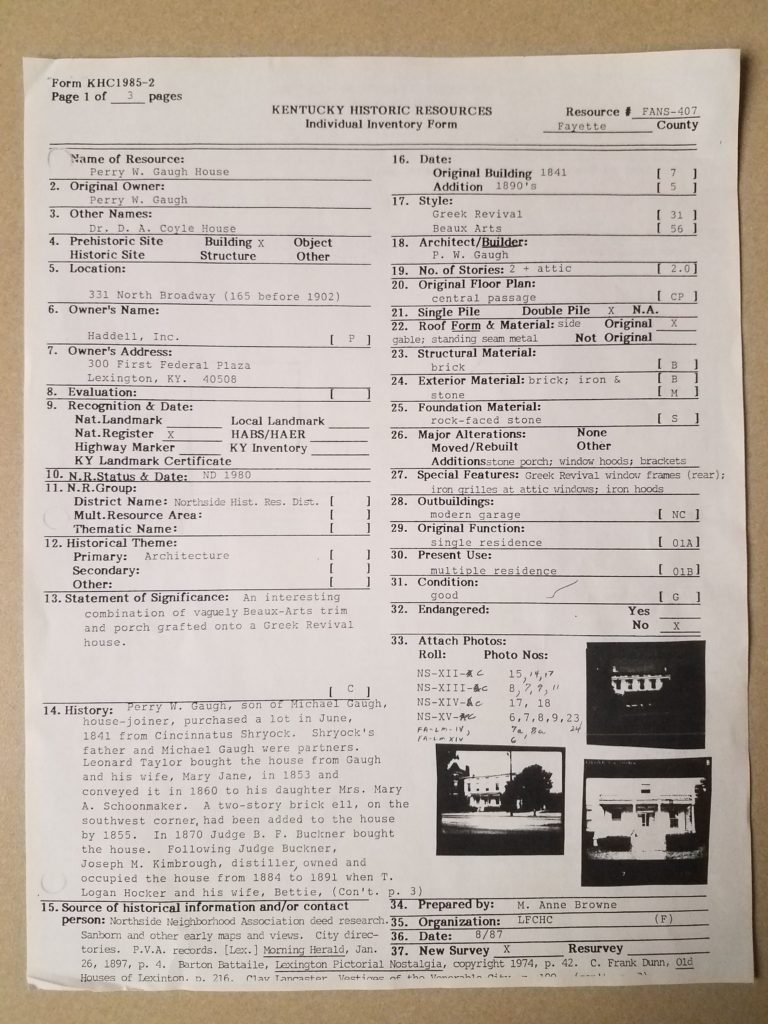

Through a helpful online resource from the Northside Neighborhood Association, and from Kentucky historian C. Frank Dunn’s book ‘Old Houses of Lexington,’ I found out that 331 was built in 1841 “by and for” a man named Perry W. Gaugh.

Gaugh was a carpenter by trade, and designed the whole house himself in the Greek Revival style popular in the antebellum time period. His family had apparently lived in Lexington for a while: his father, called the “old house-joiner,” was Michael Gaugh, a business partner of the architect and Maryland native Captain Mathias Shryock. Perry Gaugh bought the land for the house from Cincinnatus Shryock, Mathias’ son, who was also a well-known architect.

If the Shryock family name sounds familiar to you, it’s probably because you know the name of Gideon Shryock, who designed and rebuilt Old Morrison after it was destroyed by fire. Gideon was Cincinnatus’s older brother. He was the third child of Mathias and his wife Mary, who settled in Lexington in the late 1780s.

The Shryock family home used to be located on the land where Transylvania University sits now. The Gaugh and Shryock families were apparently very close. For example, Mary Shryock’s maiden name is Gaugh. Perhaps she was Michael’s sister – but I had to resist digging too deeply into family trees. The family connections in historic North Lexington are endless.

Based on the snippet from Dunn’s ‘Old Houses,’ in 1853 the house passed to a Lexington merchant named Leonard Taylor, who granted it to his daughter, Mrs. Mary A. Schoonmaker. But there was a problem: Mary A. Schoonmaker was nowhere to be found.

According to Find A Grave – a surprisingly useful tool throughout this search – Leonard had a sister named Mary Green, and a daughter named Mary Spencer, but “Schoonmaker” appears nowhere.

I was also at the end of the deed chain. Dunn’s book gave no ownership information past 1853. I thought to myself, “Well, I could settle for what I found, or I could go all out.” Guess what I chose?

City Directories

I sent a short email to the folks in the Kentucky Room at the Lexington Public Library, asking for any information they had on the house’s ownership after Leonard Taylor. Their email reference librarian, JP, emailed me right back with more than enough information from the city directories archived in the room. Sure enough, a ‘Mary A. Schoonmaker’ had never been listed at the house’s address.

According to the directories, Mr. Taylor lived in the “house west side Broadway between 3d and 4th” until as late as 1865. This makes sense, because this is the year he died. His widow, Ann, is listed at the address – now numbered “202” – as late as 1878. This also makes sense; Ann Taylor died in 1879, and there is no “Taylor” on the next directory listing in 1881.

The next directory record comes in 1887, when the house number is now “165” and a man named J.M. Kimbrough lives there.

According to the website of the Lexington History Museum, Kimbrough moved to Lexington in 1879 (in his late 20’s) to become manager of the Ashland Distillery. He stayed manager until he died at age 39, of typhoid fever, in 1890.

Kimbrough was active in the Lexington community. He helped found the Chamber of Commerce, served on City Council and, interestingly, was appointed a director of the Eastern Kentucky Lunatic Asylum a couple blocks north of 331.

Kimbrough may have risen further in Lexington government ranks were it not for his unexpected early death. I’ll admit, I was a little sad when I realized what a short life he’d lived.

The 1893 directory lists a man named T.L. Hocker at 165. Tillman Logan Hocker was mentioned in one place on the Lexington History website, as the short-lived President of Headley & Peck Distilling Company, Inc. He probably got the job from his father, James Hocker, one of Headley’s banking partners.

He became president in 1891, and they did two seasons of brewing. Then the Panic of 1893 happened. Hocker resigned on New Year’s Day the following year because they were unable to pay his salary.

Not shockingly, the next year, 1895, lists a Dr. D.A. Coyle at the 165 address. Coyle appears in the next and final Kentucky Room directory in 1902. The directory states the following about that year:

“In the spring of 1901 the City Council passed an ordinance authorizing the marking of all streets by suitable metallic signs at the corners and ordered the re-numbering of all buildings throughout the city on the plan in vogue in the principal cities of the country…and is commonly called the ‘Pennsylvania’ plan.”

Thus, 165 became 331. This change is fortuitously noted, putting “165” in parentheses after Coyle’s listing.

JP’s email was an excellent starting point, but now I was left with a few gaps: the resident from 1879-1887 and the residents after 1902. I knew I had to get away from the computer screen if I wanted to get a complete picture.

Gathering documents

One Sunday, I walked over to the public library to visit the Kentucky Room in person. One of the workers there, David, pointed me in a couple directions.

First, I was introduced to the paper archives: the directories JP had perused for me, the Sanborn fire maps, history books like Dunn’s. Then, he showed me the Property Value Administration’s online archive search tool. But what was most helpful was his advice to go next door to the PVA itself. So, that’s where I went next.

After walking through a half-broken door, turning over my license to an old security guard and sticking a printed name badge to my shoulder, I was pointed to the sixth floor of the County Government Office. In a matter of minutes after arriving on the floor, a friendly employee had scanned and printed the deed transfer records for me from 1963 to 1991.

She suggested I try the Historical Preservation office on the second floor for more dated information. After creeping through some long, fluorescent, yellowed hallways, I found the cozy office tucked in a corner, decorated with framed photos of historic Lexington.

I waited for a distant voice to finish its phone call and then rang the bell for an employee. A tall man with a goatee came around the corner. I asked if he had information on the ownership of an old house, and he replied that their office doesn’t work with record-keeping so much as it works to fulfill Kentucky’s requirements under the National Historic Preservation Act.

I was about to thank him and walk away when he asked me what I was researching. After I explained a little further, he said he may have something useful. He walked back into a storage room and came back with a binder filled with historical inventory records compiled in 1984.

One of these documents was an individual inventory form for the “Perry W. Gaugh House.” One glance told me it would be useful. While he scanned the document for me, we discussed the emotional aspects of historical research.

“You get really invested in the lives of the people you read about,” he said, in paraphrase. “You get sad when something happens to them.”

“Yeah, you read that someone died of typhus when they were 40, and you say, ‘aw, that’s sad,'” I replied, in paraphrase, referring to Kimbrough.

I then thanked the employee and headed back to LexPub to start filling in the gaps.

Filling in the gaps

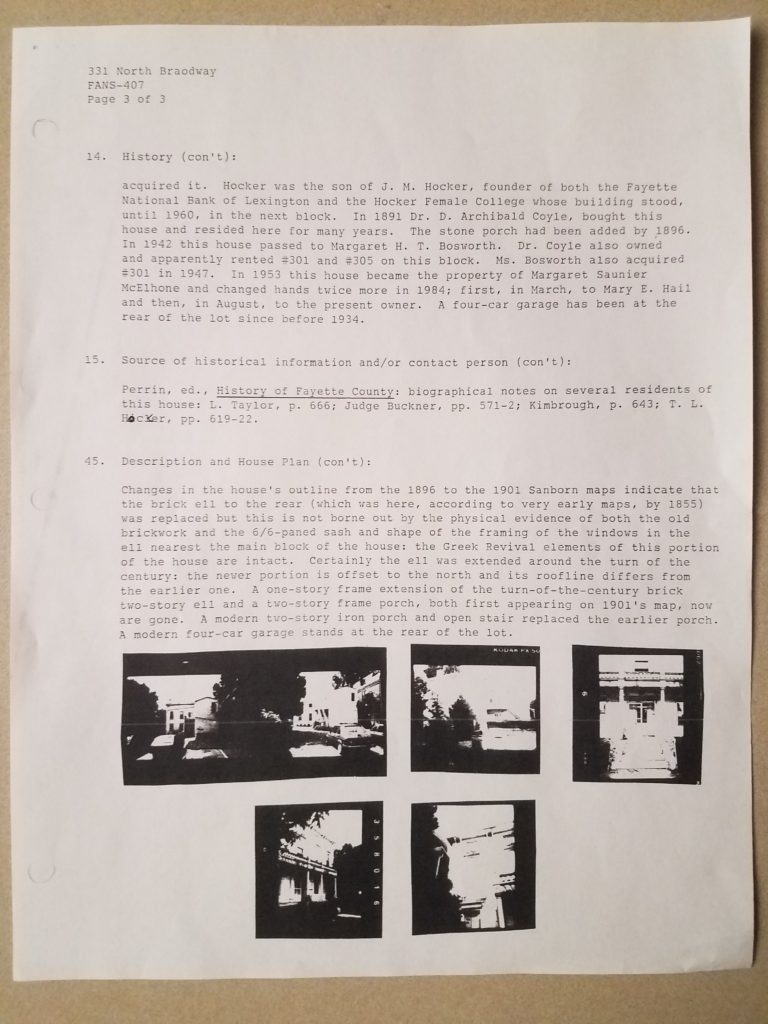

The inventory form turned out to be exactly what I needed to complete the history of the house’s ownership between 1853 and 1963. Section 14 of the form gave a very brief history of the house all the way from 1841 to 1984, sourced by the Northside Neighborhood Association’s deed research, the Sanborn maps, the city directories, PVA records, Dunn’s ‘Old Houses,’ and other sources I hadn’t yet come across.

The record confirms the house’s origins and also states that Leonard Taylor bought the house in 1853. However, instead of living in the house until his death in 1865, he had apparently “conveyed it in 1860 to his daughter Mrs. Mary A. Schoonmaker.” There was that name again.

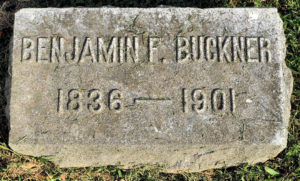

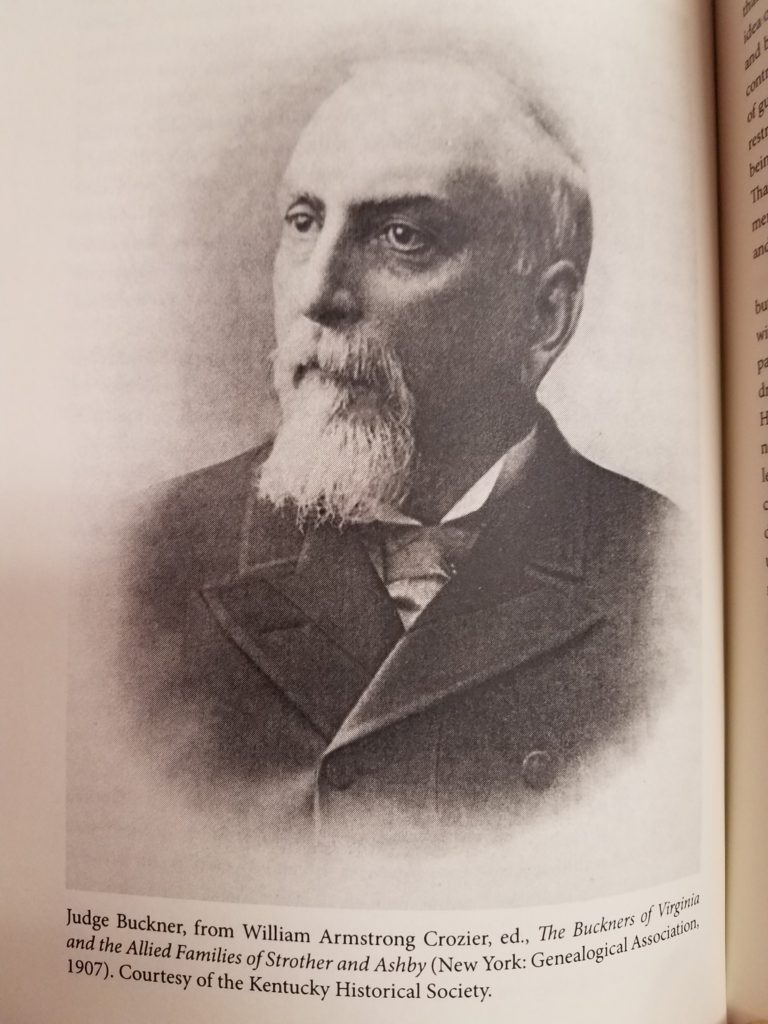

According to Section 14, Ann Taylor did not live in the house until 1878 as the city directory information had led me to believe. Instead, Judge B. F. Buckner bought it in 1870. With the help of a few web searches and the Transy library’s copy of Patrick A. Lewis’s biography of Buckner – “For Slavery and Union” – I discovered that Benjamin Forsythe Buckner was an incredibly big name among Kentucky elites during and after the Civil War.

Buckner was a slave owner from Winchester, Kentucky, but fought for the Union during the Civil War. According to the synopsis of Lewis’s biography, he was “convinced that the Peculiar Institution could not survive a war for southern independence.” So, against the wishes of his Confederate-supporting fiancee Helen and her family, he enlisted in the Union infantry in 1861.

The Emancipation Proclamation crossed the line for Buckner, though, and he resigned his military post to go back to his law practice in Winchester. But according to Lewis’s text on page 163, “Buckner’s legal career had grown bigger than Winchester by 1870…It was a wise move, then, to relocate across the county line into Lexington.” Thus, putting two and two together, Judge Buckner must have relocated his wife and two daughters to the 165 house he bought in 1870.

So, if Buckner lived in the house starting in 1870, what of Ann Taylor, Leonard’s widow? Perhaps JP’s original email incorrectly stated that 202 was the same house as Perry W. Gaugh’s, and Ann was living in a 202 elsewhere. Perhaps Buckner’s house was still listed under Ann’s name for some reason. Or, perhaps the inventory form was incorrect. Either way, Lewis’s biography states that Buckner eventually retired to a quiet life in Winchester, leaving the house at some point for the next resident.

Kimbrough was the person who moved in next, living there from 1884 to 1891 according to the form. He was indeed followed by Hocker and his wife in 1891, and then by Dr. Coyle in 1891.

Wait – something was off. Both Hocker and Coyle couldn’t have acquired the house in 1891. Perhaps this was a typo on the form. It was at this point that I realized how exhausting historical research can be in a world of human error. Either way, Dr. D. Archibald Coyle was certainly the resident of 165 in 1895, and remained its resident through 1902, when the house became 331.

I learned little about Dr. Coyle, not even an obituary. This was such a shame, as in the past I have been able to find out so much about historical figures using online obituary archives. Normally, online genealogy resources such as Genealogy Bank have plenty of newspaper obituary articles that can be used for research purposes.

That being said, according to an inventory form I found, he lived in the house for a long time, and rented a couple other houses on the block. He passed away in 1837, and the house apparently wasn’t acquired again until 1942. It seems likely that Dr. Coyle lived in the house until his passing. Perhaps his is the ghost my roommates keep referencing.

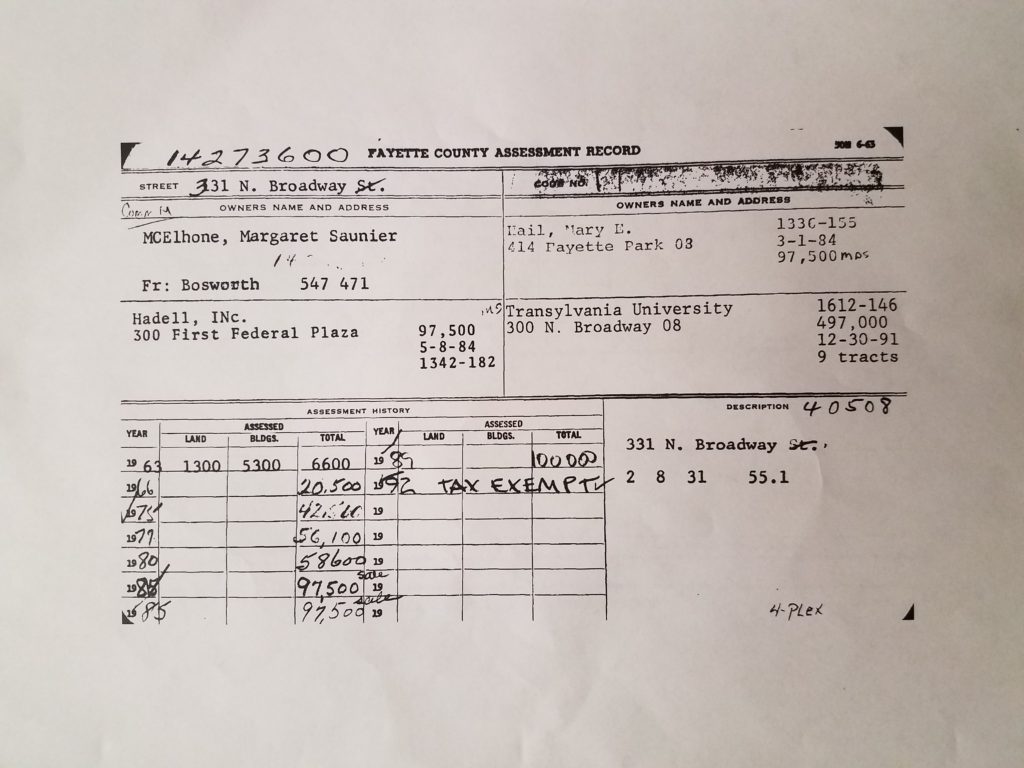

According to the form, “Margaret H. T. Bosworth” acquired 331 in 1942, succeeded by “Margaret Saunier McElhone” in 1953 and then “Mary E. Hail” in 1984. After this, the deed from the PVA notes that a company called “Hadell, Inc” acquired the house later in 1984 and remained its owner until Transylvania bought it in 1992. These names didn’t seem significant when I first read them. But I was about to get a lesson in making assumptions.

Hadell, Incorporated

Once again, it was back to searching the web. The first name that struck my curiosity was Hadell, Inc. What in the world was that? And why would a company buy a residential house?

An ad-ridden website called Bizapedia revealed that Hadell was listed as a for-profit corporation from February 1984 to October 1992. Its four principles were Homer A. Hail, J. C. Codell Jr., R Winn Turney and former Transylvania President Charles L. Shearer.

All I could find online were clues as to what exactly the purpose of Hadell was. I started by researching each of the principle organizers:

- Charles Shearer became Transy’s president in 1983. Hadell formed and bought the 331 house in 1984. Under his tenure, Transylvania saw its endowment increase from $33 million to $115 million and saw the construction of twelve new campus buildings.

- Homer Allen Hail directed the Kentucky Mortgage Company in Florida. He passed away in 1997.

- James Callaway Codell Jr. was the CEO of Codell Construction and a Transylvania trustee, sponsoring a scholarship fund in his name. He was the Chair of the Physical Plant Committee and Vice Chairman of the Board when Codell Construction built Poole Residence Hall in 1989. He passed away in 2004.

- R Winn Turney is a lawyer whose firm specializes in, among other things, estates, business and corporate law. He was a 1965 graduate of Transylvania, received a law degree from UK, and is now the Commissioner of the Kentucky Department of Aviation.

From these clues, I hypothesized the following: a brand new university president, a mortgage specialist, a construction company CEO and a corporate lawyer got together to purchase land and buildings on which to start Transy on a development spree. And, its name is a combination of two of its principles’ names: Hail and Codell. But I was still confused: Hadell was a for-profit business. So, where was the profit going? Or, was my question misguided?

Most importantly, why would this company buy the house? The house was purchased and sold in the same years that Hadell was incorporated and dissolved, so it seems plausible that the house was closely related to Hadell in some way. I pieced together more of this mystery later on.

Margaret, Margaret and Mary

The names of the three owners of the house from 1942-1984 weren’t engraved into history like many of their counterparts, but their recency only brought them more to life.

“Margaret H. T. Bosworth” is actually Margaret H. Y. (Helen Yundt) Bosworth, a New Orleans native and wife of Henry Muldrow Bosworth III. She acquired the house in 1942, but it’s unclear whether she actually lived there. Like Dr. Coyle, she rented out another house on the block. Her husband passed away in 1978 at the age of 58. Then comes the fact that startled me the most about Mrs. Bosworth: she passed away on Sunday, March 27, 2016. She passed away seven months ago. She was 94.

In a condolence on her Herald-Leader Obituary, a man named James Swisher of Lexington wrote, “Equitable agent in 1960’s. Pleasant memories.”

***

Margaret Saunier McElhone moved in in 1953 – 100 years after Leonard Taylor bought the house from Perry Gaugh. This was five years after the death of her husband, Andrew, whom she survived by 40 years to the age of 89. She passed away in 1988, four years after the house had been sold to Mary Hail.

Mary Ewing Hail was a short-lived tenant, however. According to Find A Grave, Mary’s full name is “Mary Ewing Turner Hail.” She was the wife of Homer Hail, one of the directors of Hadell. Interestingly, according to the deed from the PVA, the house was purchased in Mary’s name on March 1, 1884, and purchased in Hadell’s name on May 8, 1984. So, Hadell, Inc. bought the house from Homer’s wife after three months. This definitely couldn’t be a coincidence, but I was at a loss for how to proceed.

I soon discovered that there was much the websites and documents weren’t telling me. It was time to leave the map and get on the territory. Visiting the graves of Margaret, Margaret and Mary, as well as Homer, Archie and Logan, added the final pieces to the puzzle, and the final chapter to my search.

Cemetery Revelations

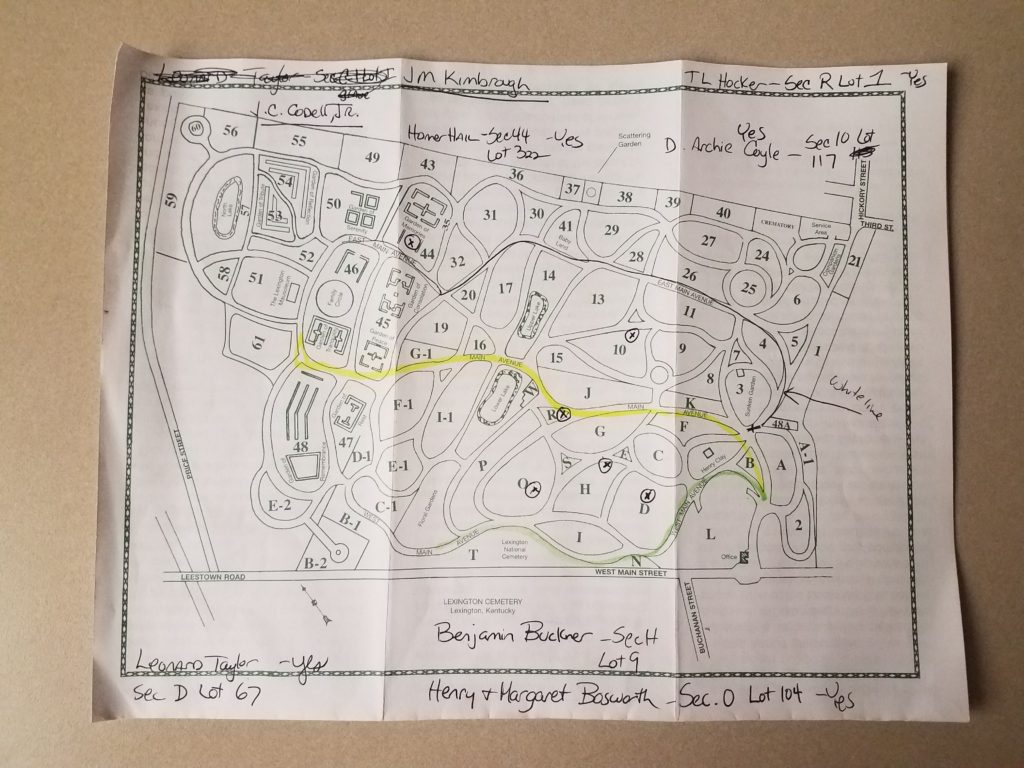

On an early Monday morning before my 9:30 class, I walked to the Lexington Cemetery office and asked for the locations of all the people I knew were buried there from Find A Grave. They were able to mark all five gravesites on a map.

I was eager to get out and explore, but class bid me to take an Uber back to campus. Later that day, I grabbed the camera and some documents from the house and asked my roommate, junior Kacy Hines, to come along. This time, I drove. With map in Kacy’s hand and camera in mine, we embarked to find our deceased housemates.

First, we found T. Logan Hocker, buried by his wife. “Logan, my man!” I exclaimed. Turning to Kacy, I said, “This is more emotionally impactful than I thought it would be.”

Next we found Mrs. Bosworth, buried beneath a shiny new stone next to her husband, a World War II veteran. I would’ve walked right past her had I not known her maiden name, Yundt, because “Margaret” apparently went by Helen.

Kacy found it cute that the pair had matching symbols on their headstones. The difference in the age of headstones between husband and wife saddened me. It seems a common trope, the wife outliving the husband by many years. And she was buried less than a year ago – what closeness I felt. To think if we had done our research just a year ago, we might have interviewed her.

Next, Kacy and I successfully searched long and hard for Leonard Taylor and discovered a major piece of the puzzle. There were Schoonmakers buried among the Taylors.

There was still no Mary A. Schoonmaker, only a Sarah A. and one other; however, Mary Spencer, Leonard’s daughter, was also buried here with her husband Wesley.

So, long story short, C. Frank Dunn seems to have been mistaken. The house was either conveyed to Mary Spencer, or to this mysterious Sarah A. Schoonmaker: not Mary A. Schoonmaker. I forgive him: siblings’ names are easy to confuse. But now, there’s a new mystery to solve.

After these three, we hopped back in my car and drove further into the cemetery to find Dr. Coyle and the Hails. As we paid our homage to Dr. Coyle, I mentioned that he was likely to have died in the house. “So you’re the ghost that’s messing with us, huh?” she asked, in paraphrase.

Lastly, we found the Hails. A large stone marked the family plot.

Below, I was greeted with yet another revelation. Remember “Mary Ewing Turner Hail” from the Find A Grave listing? This was a misspelling.

One of Mary’s names isn’t Turner, but Turney. Mary Hail was related to R Winn Turney, a principle of Hadell, Inc along with her husband, Homer. This reminded me of the closeness between the Gaugh and Shryock families. Mary Gaugh Shryock and Mary Ewing Turney Hail even had the same first name. Inter-family ties have clearly run strong in wealthy Lexington circles for a long time.

Before heading across Main Street to the Calvary Cemetery to find Mrs. McElhone’s burial place, Kacy and I stopped to rest by a lake. While there, I received a reply email from David O’Neill at the PVA. While he didn’t quite answer my inquiry about the purpose of Hadell and why they had bought the house – he sent me a link to a website I’d already raided for info – he did say that “Hadell is one of your holding companies.” According to a Google search, this means “a company created to buy and possess the shares of other companies, which it then controls.”

So, Hadell was likely formed to “hold” Transylvania’s investments, so that it could grow Transylvania’s endowment through stock shares. Smart move from Shearer, a brand new president with an economics background.

But that still left the question of why Homer’s wife bought the house in March of 1984. And why Hadell bought the house in 1984. And why Transylvania acquired the house the year Hadell dissolved. These are questions I pondered aloud as Kacy and I gazed out on the lake.

We saw a fish. We named it Hail.

Echoes of history

On the drive back to 331 after visiting the site of Mrs. McElhone in Calvary Cemetery, I asked Kacy where she heard that 331 was an African-American college. We couldn’t find the original source, and I saw no evidence in my own digging that the house was ever an educational institution – except for the house’s tenure as a living-learning community for students of foreign languages.

To complete the picture of Hadell, I attempted to call what I thought was the office of R Winn Turney, but the number went straight to some case management company. There are still questions I’d like to ask him about Hadell’s use of the house, and about his relationship to Mary E. Turney Hail.

Additionally, I spoke with President Seamus Carey’s Executive Assistant, Rachel Millard, who is helping me get in contact with Charles Shearer so he can provide more information on Hadell’s formation and relationship to the house. I’ll be sure to share my findings.

***

My goal throughout this search wasn’t to write a history paper. My goal wasn’t to come out of this with a “complete history of the 331 house.” My goal was to discover more about the people who lived in the house before me, and before my housemates.

So while I didn’t answer all of my questions or fill in all the gaps, I’m now more aware of the past’s reflection on the present. And I became more intrigued by Lexington history than I ever thought I would. I hope my adventure inspires others to discover the history surrounding them – quite literally – every day.