This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article. The original article was written by Kyle Greenwalt, Associate Professor, Michigan State University.

The centennial of the end of World War I is reminding Americans of a conflict that is rarely mentioned these days.

In Hungary, for example, World War I is often remembered for the Treaty of Trianon, a peace treaty that ended Hungarian involvement in the war and cost Hungary two-thirds of its territory. The treaty continues to be a source of outrage for Hungarian nationalists.

In the United States, by contrast, the war is primarily remembered in a positive light. President Woodrow Wilson intervened on the side of the victors, using idealistic language about making the world “safe for democracy.” The United States lost relatively few soldiers in comparison to other nations.

As a professor of social studies education, I’ve noticed that the way in which “the war to end war” is taught in American classrooms has a lot to do with what we think it means to be an American today.

As one of the first wars fought on a truly global scale, World War I is taught in two different courses, with two different missions: U.S. history courses and world history courses. Two versions of World War I emerge in these two courses – and they tell us as much about the present as they do about the past.

WWI: National history

In an academic sense, history is not simply the past, but the tools we use to study it – it is the process of historical inquiry. Over the course of the discipline’s development, the study of history became deeply entangled with the study of nations. It became “partitioned”: American history, French history, Chinese history.

This way of dividing the past reinforces ideas of who a people are and what they stand for. In the U.S., our national historical narrative has often been taught to schoolchildren as one where more and more Americans gain more and more rights and opportunities. The goal of teaching American history has long been the creation of citizens who are loyal to this narrative and are willing to take action to support it.

When history is taught in this way, teachers and students can easily draw boundaries between “us” and “them.” There is a clear line between domestic and foreign policy. Some historians have criticized this view of the nation as a natural container for the events of the past.

When students are taught this nationalist view of the past, it’s possible to see the United States and its relationship to World War I in a particular light. Initially an outsider to World War I, the United States would join only when provoked by Germany. U.S. intervention was justified in terms of making the world safe for democracy. American demands for peace were largely based on altruistic motives.

When taught in this manner, World War I signals the arrival of the United States on the global stage – as defenders of democracy and agents for global peace.

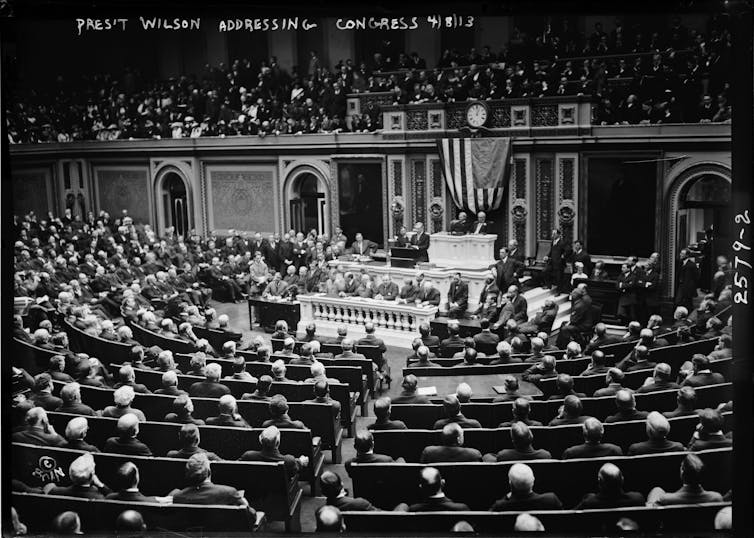

Bain News Service / Library of Congress [LC-B2- 2579-2]

WWI: World history

World history is a relatively new area of study in the field of historical inquiry, gaining particular ground in the 1980s. Its addition to the curriculum of American schools is even more recent.

The world history curriculum has tended to focus on the ways in which economic, cultural and technological processes have led to increasingly close global interconnections. As a classic example, a study of the Silk Road reveals the ways in which goods (like horses), ideas (like Buddhism), plants (like bread wheat) and diseases (like plague) were spread across larger and larger areas of the globe.

World history curricula do not deny the importance of nations, but neither do they assume that nation-states are the primary actors on the historical stage. Rather, it is the processes themselves – trade, war, cultural diffusion – that often take center stage in the story. The line between “domestic” and “foreign” – “us” and “them” – is blurred in such examples.

When the work of world historians is incorporated into the school curriculum, the stated goal is most often global understanding. In the case of World War I, it’s possible to tell a story about increasing industrialism, imperialism and competition for global markets, as well as the deadly integration of new technologies into battle, such as tanks, airplanes, poison gas, submarines and machine guns.

In all of this, U.S. citizens are historical actors caught up in the same pressures and trends as everyone else across the globe.

The US school curriculum and World War I

These two trends within the field of historical inquiry are each reflected in the American school curriculum. In most states, both U.S. history and world history are required subjects. In this way, World War I becomes a fascinating case study of how the same event can be taught in different ways, for two different purposes.

To demonstrate this, I’ve pulled content standards from three large states, each from a different region of the United States – Michigan, California and Texas – to illustrate their treatment of World War I.

In U.S. history, the content standards of all three states place World War I within the rise of the United States as a world power. In all three sets of state standards, students are expected to learn about World War I in relationship to American expansion into such places as Puerto Rico, the Philippines and Hawaii. The ways in which the war challenged a tradition of avoiding foreign entanglements is given attention in each set of standards.

By contrast, the world history standards of all three states place World War I under its own heading, asking students to examine the war’s causes and consequences. All three sets of state standards reference large-scale historical processes as the causes of the war, including nationalism, imperialism and militarism. Sometimes the U.S. is mentioned, and sometimes it’s not.

And so, students are learning about World War I in two very different ways. In the more nationalistic U.S. history curriculum, the United States is the defender of global order and democracy. In the world history context, the United States is mentioned hardly at all, and impersonal global forces take center stage.

Whose history? Which America?

Scholars today continue to debate the wisdom of President Wilson’s moral diplomacy – that is, the moral and altruistic language (like making the world “safe for democracy”) that justified U.S. involvement in World War I. At the same time, a recent poll by the Pew Research Center has shown that the American public has deep concerns about the policy of promoting democracy abroad.

In an age when protectionism, isolationism and nationalism are seemingly on the rise, our country as a whole is questioning the relationship between the United States and the rest of the world.

This is the present-day context in which students are left to learn about the past – and, in particular, World War I. How might their study of this past shape their attitudes toward the present?

History teachers are therefore left with a dilemma: teach toward national or global citizenship? Is world history something that happened “over there,” or is it something that happens “right here,” too?

In my own view, it seems incomplete to teach just one of these conflicting views of World War I. Instead, I would recommend to history teachers that they explore competing perspectives of the past with their students.

How do Hungarians, for example, generally remember World War I? Or how about Germans? How about the Irish? Armenians? How do these perspectives compare to American memories? Where is fact and where is fiction?

Such a history class would encourage students to examine how the present and the past are connected – and might satisfy both nationalists and globalists alike.