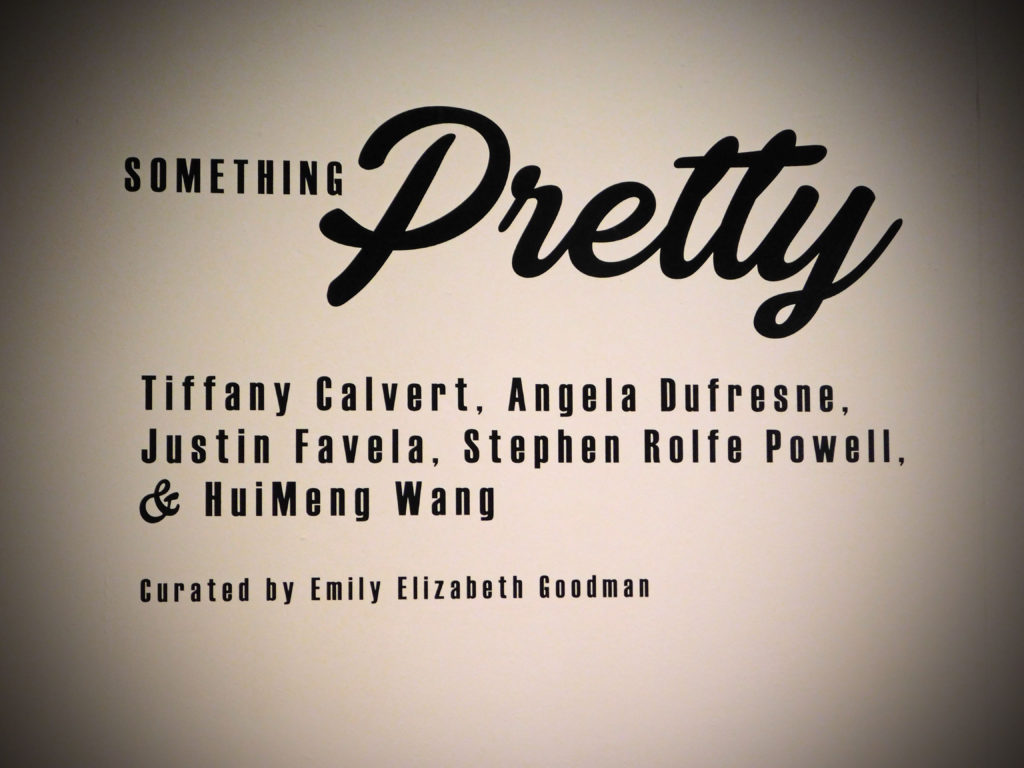

Walking into Transylvania’s Morlan Gallery to see “Something Pretty” is reminiscent of happening upon a field of wildflowers. Suddenly, the atmosphere becomes ethereal, suspending a surreal glow over scatterings of pieces by Tiffany Calvert, Angela Dufresne, Justin Favela, Stephen Rolfe Powell, and HuiMeng Wang.

In the words of curator Dr. Emily Goodman, “this exhibition seeks to complicate what it means to be pretty, by bringing together several different artists whose work engages with the aesthetics of prettiness, while simultaneously undercutting the diminutive and dismissive connotations of the label.”

Each artist’s unique style is able to exist individually, but integrates into a cohesive message. The most dynamic pieces are those of Stephen Rolfe Powell, a renowned glass artist. “Aloof Whispering Cyclone” is indeed a tornado of color. It recalls abstract expressionism, a swirl of complementary shades that kisses its base like a raindrop meeting a puddle. His work is layered, making it visually delicious upon closer inspection.

Justin Favela’s piñata pieces are also layered, but in a different sense. Up close, they are nothing but brightly colored strips of paper adhered to cardboard, but given space, they become mosaics. Favela’s work addresses myths surrounding the idealization of Mexico “as a pastoral idyll.”

Similarly, some of Tiffany Calvert’s work utilizes non-traditional medium, including foam insulation board. One such piece is “Untitled #297,” whose clunky, fragmented brushstrokes give the impression that the image is falling apart, or possibly, coming together. She also explores the relationship between traditional and digital media in “Untitled #286” and “Untitled #305.” Using oil on a digitally printed canvas, she creates “unseeable” images, meaning that viewers cannot determine “whether they are looking at a photograph or an abstraction.”

Angela Dufresne also uses thickly applied brushstrokes in her oil paintings, creating a textural energy. “Listen To Me You Idiot” depicts a grotesque yet endearing figure emerging from painterly strokes, complicating ideas about beauty and humanness. She also explores gender and sexuality in “Jan,” an oil painting of a masculine figure who seems to be rejoicing amidst Dufresne’s muddied application of paint.

The show’s film component takes shape in “You Are Beautiful You Should Be Seen,” by HuiMeng Wang. For three minutes and 34 seconds, scenes of a beach expedition to uncover tree trunks that were supposed to have been shipwrecks fill the screen. Why? It is a rumination on uncertainty and beauty. These pieces are the individual flowers of a larger bouquet offered to the viewer. It is up to to us to either accept or reject their meaning.

As a woman living in the Digital Age, I am well acquainted with expectations and conceptions of beauty. Each work featured in “Something Pretty” speaks to a different aspect of what it means to be “pretty” and how “pretty” things are treated.

Powell’s glasswork meets the viewer at the door, establishing the undeniable prettiness of what is delicate, yet I also find beauty in its boldness and intricacy. The political and social commentary that Favela’s piñata paintings provide are a different conversation entirely. “Valle de México desde el Río de los Morales, After Jose Maria Velasco” may essentially take the form of a commercialized traditional Hispanic craft, but this is what makes it appealing. Favela refuses to allow his culture to be romanticized by turning an instrument of that romanticization into art. Here, the beauty lies in the message.

Dufresne’s pieces from her “Muses and Monsters” series spark a similar conversation. They feature anthropomorphic creatures that are not pretty in the traditional sense. Yet they possess undeniable feminine characteristics. I found myself sympathetic to their plight, their inability to ascend to true beauty.

The simplicity of Calvert’s non-digital pieces wore off the longer I looked at them. “Untitled #267” evoked uncomfortableness, as if she was hurriedly trying to cover what was on the canvas with slashes of black and gray. The larger paintings, in which she combines oil and digital prints, appear to be glitched, as if she was interrupted mid-brushstroke. “Untitled #305” features flowers, a conventionally pretty still life component, yet their status is elevated to beautiful because of Calvert’s unique interpretation.

Prettiness is best described by “You Are Beautiful You Should Be Seen,” in which the dazzlingly white tree trunks are lost in sand, unable to be restored to their former state. The dreamlike quality of the film casts a serenity over the show, reminding viewers to revel in what is there before it disappears.

“Something Pretty” should be seen by anyone interested in aesthetic standards and the connotations of prettiness. If we are to deem something pretty, is it better that we not say anything at all? Viewers should walk away knowing whether or not they are comfortable with being assigned and assigning the term.

In exposing ourselves to the work of the featured artists, we become part of a larger conversation surrounding beauty. The undeniable feminist qualities of the exhibit present the opportunity for rumination not just for members of specific niches, but for everyone. It is often assumed that art appreciation is reserved only for the elitist and educated, but appreciation is not actually a requirement. Everyone should feel welcome and included in the discussions “Something Pretty” sparks, because if that is not the case, there is no use in having a discussion at all.

Though the exhibit deconstructs traditional prettiness, there is nothing traditional about the artwork featured. Taking what has been marginalized and making it the focus of an exhibition may not be a universally appealing concept. But it challenges the fundamental lenses through which we understand art. Even if we think art is just “something pretty,” we are participating in the discussion.