Since taking office, President Trump has mobilized U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) and Customs and Border Protection (CBP) to carry out an unprecedented mass deportation agenda, so far removing 230,000 people from the country. Countless others have been detained and incarcerated by ICE while awaiting the adjudication of their cases.

A heavy ICE presence in cities where many residents don’t want them has also led to tense clashes in the streets. On January 7, an ICE officer fatally shot U.S. citizen Renee Nicole Good in Minneapolis.

Immigrant families across the country have been living in a state of fear and high alert. The Rambler spoke with a number of immigrants in the Lexington community who asked to remain anonymous for fear of reprisal from federal immigration authorities.

One local green card holder said that it had become clear that nothing can guarantee safety, not even American citizenship. “Do we comply or not comply if ICE questions us, detains us, harasses us?” they asked. “What does complying even mean?” Another said they have stopped speaking Spanish in public and are now afraid to go to work.

Transy President Brien Lewis said that his administration is monitoring the situation closely and will “share updates with the campus community as appropriate.”

The university, he said, “complies with all applicable federal and state laws and is committed to protecting the privacy of our community.”

After the Good shooting, hundreds of anti-ICE protests took place nationwide, including in downtown Lexington. Immigration advocates in the city and members of the Transy community are now scrambling to answer the question: What’s next? Could the chaos in Minneapolis and other communities come here?

Tracking ICE

For immigrant families in Lexington, one of the most challenging aspects of Trump’s ICE surge is the uncertainty: It’s next to impossible to predict just when and where ICE agents might show up.

As with communities across the country, individuals and advocacy groups periodically post warnings on social media about the presence of ICE in certain neighborhoods or surrounding cities. In some cities, DIY social media accounts or new grassroots activists have led highly effective responses, and at times have been more nimble or deeply plugged into information on the ground than established immigrant-rights institutions.

But many of the social media warnings are unverified, and may turn out to be false. People desperate for answers are sometimes confronted with rabbit holes of potential misinformation, furthering anxieties.

“Sharing unconfirmed ICE sightings creates fear and causes real harm to people who miss work, school, medical appointments, and even appointments because of unconfirmed activity,” said Executive Director of Neighbors Immigration Clinic, Mizari Suárez. She said that the only two ICE hotlines that people should trust are Louisville SURJ (Showing Up for Racial Justice) and Neighbors Immigration Clinic. “We are actively sending trained volunteers to verify and respond,” she said.

Adding to the confusion, even the data about past ICE activities is extremely difficult for the average citizen to understand. ICE has field offices in Louisville and Bowling Green, so there is nothing unusual about the presence of ICE officers in Kentucky. Since Trump took office, their activities have increased: According to the Kentucky Center for Economic Policy, ICE has made 1,950 arrests between Jan. 20, 2025 to Oct. 15, 2025. In the same time frame in 2024, 1,475 arrests were made. But the concern now is an all-out surge of the kind imposed on Minneapolis, where around 2,000 agents suddenly arrived in a single city.

Kentucky represents a potentially attractive option for temporary ICE detainees. So far, 22 law enforcement agencies in the state (with more in process) have entered into special arrangements, known as Section 287(g) agreements, with federal immigration authorities. The terms of these arrangements vary. The most expansive version, known as the “task force model” and used by 18 agencies in the state, essentially deputizes state or local law enforcement agencies to make immigration arrests during routine policing. The Lexington Police Department is not currently participating in any 287(g) arrangement with ICE, but agencies in nearby cities like Georgetown, Stanton, and Winchester are.

Fear in local communities

“ICE has been in Elizabethtown, Paducah, and the South End of Louisville,” one local immigrant told us, adding that they feared a surge of agents would be in Lexington soon. Around two months ago, they said, ICE picked up and detained five people in the Cardinal Valley area in Lexington. These activities were not widely known, they said; very little information can be found about them online.

The panic in local communities has been palpable, regardless of immigration status. One naturalized citizen told us they now carry all their documentation every time they leave the house.

“My dad has his green card and had done the process, but he’s scared,” a U.S.-born citizen told us. “My parents are trying so hard to not seem worried but I can see it.”

“We have our daughter’s phone number written on our arms, just in case,” a recently naturalized mother told us.

As rumors abound, Suárez and the Neighbors Immigration Clinic work to sort between fact and fiction, responding immediately to investigate any reports, including sending volunteers to physically survey the area.

Concerned citizens can reach out to the clinic to verify whether or not a claim is true, as well as learning about rights and resources available to help keep them safe.

The clinic also has recommended guidelines for what to report if people do spot ICE in their communities, based on the acronym SALUTE (Size, Actions/Activity, Location/Direction, Uniform/Clothes, Time and Date of Observation, Equipment and Weapons). See below for a hypothetical example.

What if an ICE surge comes to Lexington?

Asked about enforcement activity in the region, a spokesperson from the ICE field office in Chicago—responsible for overseeing activities in Kentucky and five other states—replied by email: “ICE does not share mission information for security reasons.” (Prior to receiving the email response, The Rambler had also attempted to reach the field office by telephone dozens of times; each time, the line was busy.)

Sergeant Bige Towery said the Lexington Police Department was not aware of any specific ongoing or future ICE operations in Lexington.

And if an ICE surge does arrive in Lexington? “When requested, the Lexington Police Department assists all federal enforcement partners to ensure the safety of all those involved,” Towery said. “The Lexington Police Department enforces state and local laws. Any federal laws are the jurisdiction of federal agencies.”

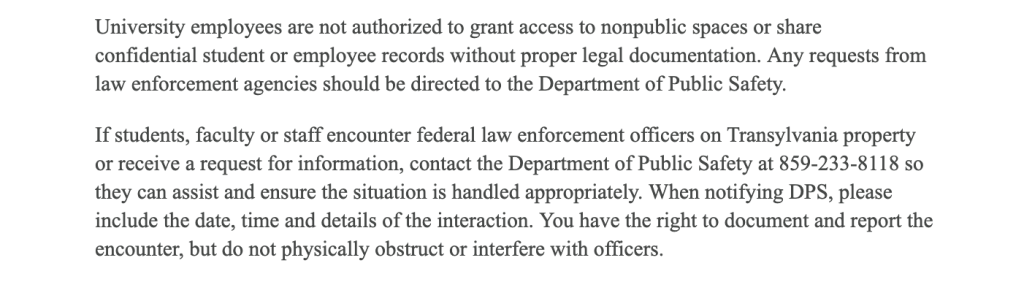

President Lewis focused on protecting the privacy rights of campus community members when possible under the law:

DPS Chief Steven Herold was unable to comment in detail before press time, but said the department has contacted Transy’s Justice and Safety Cabinet for clarification.

Because Transy is a private institution, ICE would be required to obtain a signed judicial warrant to enter the campus center or any academic or residential buildings. But nothing is stopping ICE from approaching people in public spaces. Outdoor spaces, even on Transy’s private property, may not necessarily offer constitutional protection from warrantless searches—there would typically not be a legal expectation of privacy on campus green spaces. If ICE agents are spotted on campus, advocates suggest that anyone concerned should stay inside a university building.

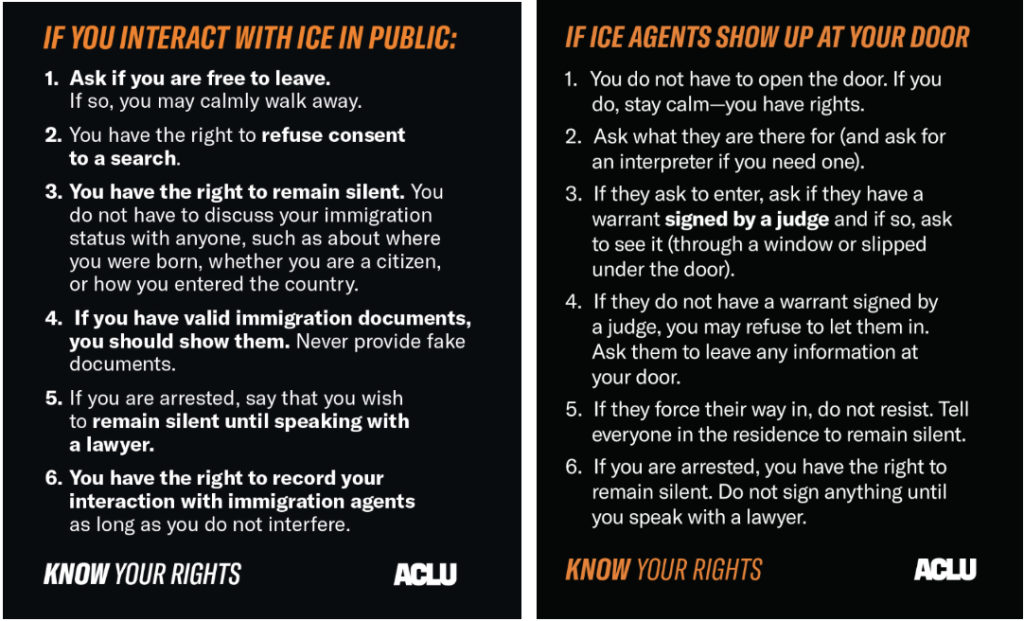

Legal advocates also emphasize that the important thing people can do to prepare is to know their constitutionally protected rights. Here are the basics from the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU), all of which apply to citizens and non-citizens residing in the U.S. alike: