“Don’t be afraid to let your body die.”

– Deborah Harry as Nicki Brand, Videodrome

From January 13th to February 21st, Morlan Gallery exhibited Allison Spence’s solo show Untitled Frankenstein. The show’s namesake comes from the iconic gothic and body horror book Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, where Dr. Victor Frankenstein never actually names the being he fashions out of repurposed body parts. Instead, the being’s humanity is forcefully stripped and rejected, bound outside of what is considered human as something unnamed or colloquially fashioned as “Frankenstein’s monster.” Questioning society’s use of moralism and the drive to categorize in order to uphold hierarchy, the show filled the gallery with faux fur, layers of motif, and linen prints. It asked us who the world wants us to see as monstrous and why.

I had the pleasure of attending Spence’s artist talk on February 20th, where she gave an overview of her creative practice and its influences on her current body of work. Beginning with a historical overview of societal taxonomy from the end of the Enlightenment period to today, Spence cited the importance of surgical history and anatomy in her current practice. Spence analyzed Thomas Eakins’s The Agnew Clinic, an oil painting depicting anatomy theater surgery noticeably without gloves or modern antiseptic procedure to a captivated audience in the 19th century; frequent references were made to body horror from Junji Ito’s Tomie to David Cronenberg’s The Fly. In these two strands of influence, a viewer can see Spence’s fascination and interrogation with how humanity is and has been defined, from surgery as a spectacle to abjection.

Spence’s own medical history also informs her work. She is informed by the conversations around bodies, from which ones are uplifted by society to which ones are demonized, what makes something ‘human’, and how a category’s strict boundaries leave an indeterminate zone both in between and outside. Spence sees these layers of thought and history along with her own fascination with body horror and the meshing of form as reminiscent of a teratoma. Latin for monstrous tumor, teratomas are masses of tissues from around the body and might also develop other ‘human’ structures such as hair or teeth, combining to form a tumor that can be either benign or cancerous. The teratoma fascinates Spence, with her defining her work “within its spectre.” Referencing and learning about teratomas for years throughout her art career, Spence also described her surprise when in 2022 she visited a doctor and found out that she had a teratoma of her own. Thus, the show represents relatively new work given this revelation, informed by her own object of fascination, the teratoma, that had ‘manifested’ in her body only three years before the talk.

When one views a body as a fixed category, a static mass with no malleability, abjection arises when that form is obscured. That is what Spence embodied in this show, and no better than with the suspended resin pieces. The current body of work is a progression of Spence’s work in grad school, a series of paintings of compressed bodies taken from snapshots of highly compressed wrestling videos. In those snapshots, Spence found an inability to distinguish between the wrestlers, instead seeing a merging of bodies, a point of interest that drew her to continue thinking about the meshing of human form.

The resin pieces are a physical crushing of the painting reminiscent of these combined human bodies. Made up of several layers calling back to Spence’s own fascination with the teratoma, she crushed images of wrestlers, machine-embroidered text on linen, digital collages of her medical images, and green faux fur while using resin to lock the painting into a sense of suspended animation. I liked how the pieces appeared to be both strained and fluid, giving them an implied movement only possible through the stretching and crushing processes Spence used to create them.

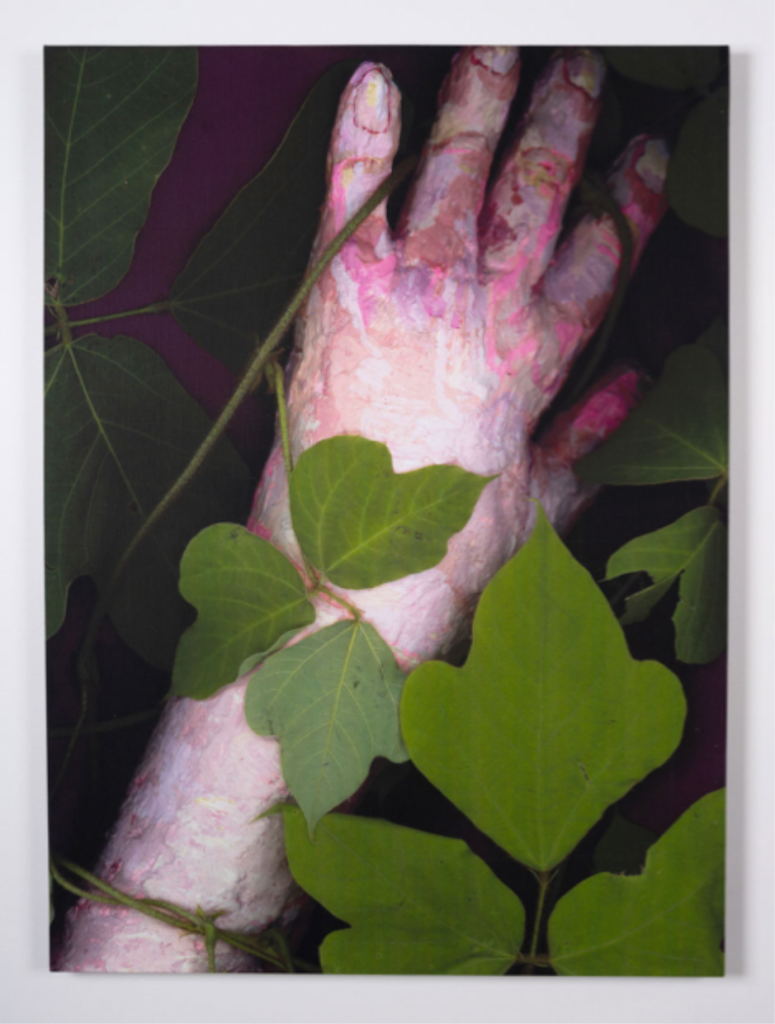

The show also discussed the ‘indeterminate’ zone of things that defy categorization. For this Spence pointed towards a series of linen prints depicting various organs in fields of kudzu. This ‘kudzu series’ was created by Spence using plaster sculptures of organs and kudzu clippings, scanned digitally to create a ‘flattened look.’ In her talk, Spence discussed how kudzu was initially introduced to the south to stop soil erosion, but now devours entire landscapes. The tension between kudzu as a threat, an invasive species to be stopped, and a symbol of the south, due to its enmeshment into the landscape, stuck with me. I have memories of going to my grandparents’ house and driving past cornfields and forests overtaken by kudzu. Because of that kudzu has overtaken my own childhood memories as well, becoming an inseparable part of those summers I spent with my grandparents, existing alongside the knowledge of its environmental impact. The organs in these pieces represent those who received an organ transplant, echoing the show’s themes around fears of what makes a body ‘whole.’ Clint Hallam in particular, represented by the piece Clint, analyzes the psychological impact of having a hand transplant. As discussed in the talk, Hallam stopped taking his rejection medicine and had his hand amputated after his body rejected it. For Spence, the transplanting of organs can mimic the inclusion of kudzu, seen as something ‘invasive’ by the body but also representing the breaking of society’s uplifting of a ‘whole’ human.

I found Untitled Frankenstein to be a highly rewarding show to attend. The attention to material and its reflection of biological processes initially piqued my interest, but visiting the gallery and hearing Spence discuss her work in detail showed me just how interdisciplinary the work was. From the kudzu pieces to draped fabric suspended in motion, Untitled Frankenstein told a story advocating against the boxes we are pressured to put ourselves into within capitalist and societal systems. I found the show to interrogate my own relationship to transness and how queer people are perceived at large. From divorcing from the heteronormative nuclear family to forging our own paths that defy the binary structures we live under every day, I found it comforting to see humanity displayed in what is often deemed ‘in-human’ or ‘un-whole.’ Spence herself echoed this when asked about queer theory’s intersections with her work during the Q&A, broadening her answer to also include discussions of disability. While she discussed that queer theory was not at the forefront of her mind when creating her body of work, she beautifully put that there is beauty in indeterminism and that there is so much more to becoming rather than strictly defining. To me that summed up the impact of art, how I could have such a visceral connection to work out of my own personal link to it, and how I could also connect to work through the artist’s own interpretations. These things can all coexist, and they can also mix together, giving each person their own experience.

You can see and read more about Allison Spence’s work at her website. Thank you to Anthony Mead for feedback on this review and to Morlan Gallery for hosting the exhibition.