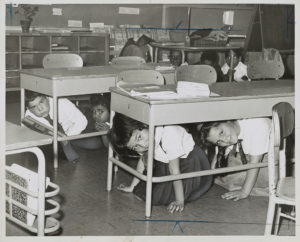

I remember the first time I thought I was going to be shot. I had come to school late that day, so I didn’t hear the announcement over the intercom. I didn’t realize that it was just another one of the seemingly endless drills we always did at the start of the school year. Fire drills, earthquake drills, for some reason tornado drills, and drills for when someone might burst into the classroom and shoot us while we hid in cupboards and closets. I was prepared—for what, I don’t know. I was only thirteen, so a vision of jumping up and tackling the gunman, playing the hero, flashed briefly through my head. I think I knew, though, that all I’d do was huddle under a desk and wait to die.

I remember the first time I shot a gun. I was eight years old, at a Cub Scout camp. We—the kids—got a choice between rowing out onto the lake or learning how to shoot a BB gun. We even got to use an airsoft mask for safety. Naturally, all of us boys immediately decided that we were never going to row crew.

I remember the Scout master making a big deal of holding the rifle correctly as it was the most powerful pellet gun. The kick was apparently very dangerous—if we weren’t careful, the butt of the rifle could pop up and break our nose. But I remember shooting for the first time and how easy it was. Hold the barrel steady, line up the tiny iron sights, exhale, and pull the trigger. I didn’t even have to wait for the satisfying hole in the paper target to appear. I could be really good at this, I thought, in the way that eight-year-olds think they can be good at anything.

None of my friends have ever been shot. I’ve never had to hold someone in my arms as they bled out onto the sidewalk. Nobody has ever pointed a gun at me and squeezed the trigger. I’ve never been rushed to the hospital with a breath mask on my face and a tourniquet holding my leg on as blood spills onto the floor of an ambulance.

People like me, who went to good middle class schools and lived in pleasant enough suburbs and have had ordinary, unremarkable lives—most of our experiences with guns are either through a video game or from something like a Scout camp. We get to be the ones shooting, tallying up our skill and precision and our feelings of power by counting the holes we put in a paper target.

The other side of our experiences is easier for us to push away. It’s pictures on the TV or posts online. Most of the time they don’t even show what the aftermath of a shooting looks like; it gets sanitized. The news shows pictures of sobbing survivors and closed caskets, and it’s easy to think that it’s not a real problem. It’s just the news; it happens to other people.

In other ways, though, we’re all under the gun. Young people, my generation, have spent the last twenty years practicing for when someone will burst into their classroom and try to kill them. We’ve seen video after video of police, the so-called good guys with guns, use them to execute innocent black men and women. And children. We know, we’ve known since we could remember, that any one of us could be shot; some of us have practically expected it to happen to one of us, sooner or later.

We pretend that it’s something we can control or fight back against. We maintain for ourselves the illusion that we’re in control of the violence or that it doesn’t really affect us. We play video games where we can customize our light machine guns and kill our friends’ avatars over and over across dozens of digital battlefields. It doesn’t matter; it’s just a game. And we can control it. This game of control, of maintaining the illusion that real life is as consequence-free as a game, is ridiculous when it’s explicit. And yet it saturates our young lives as surely as the real danger of getting shot.

Some of us take the illusion even further. Some of us tell ourselves that the weekend training course in self defense, and the little pistol we carry in our handbag, is enough to protect us. Some of us believe that. Ignore the statistics, the ones that tell you you’re the likeliest to get shot with your own gun. After all, you’re safe, you’re careful. Not like those other people, those stupid people, who got themselves shot. That won’t happen to you.

It probably won’t. Most of us are never going to be shot or even be shot at. But all of us know, deep down, we could be. And we know there’s not a damn thing any of us can do to stop it. Except, maybe, march. Except, maybe, call your Congressman, he’ll listen to you. Except, maybe, if you campaign, and protest, and vote. Maybe if we create some political danger of our own, we can do something about the endless looming danger of the barrel and the bullet. We’ve lived under the gun for long enough.

This piece is part of Under the Gun, a Rambler feature series on gun control & gun culture in the wake of mass shootings and the March for Our Lives. Read the other parts of the series here.